A timeless midcentury modern jewel gets its sparkle back, thanks to a meticulous renovation.

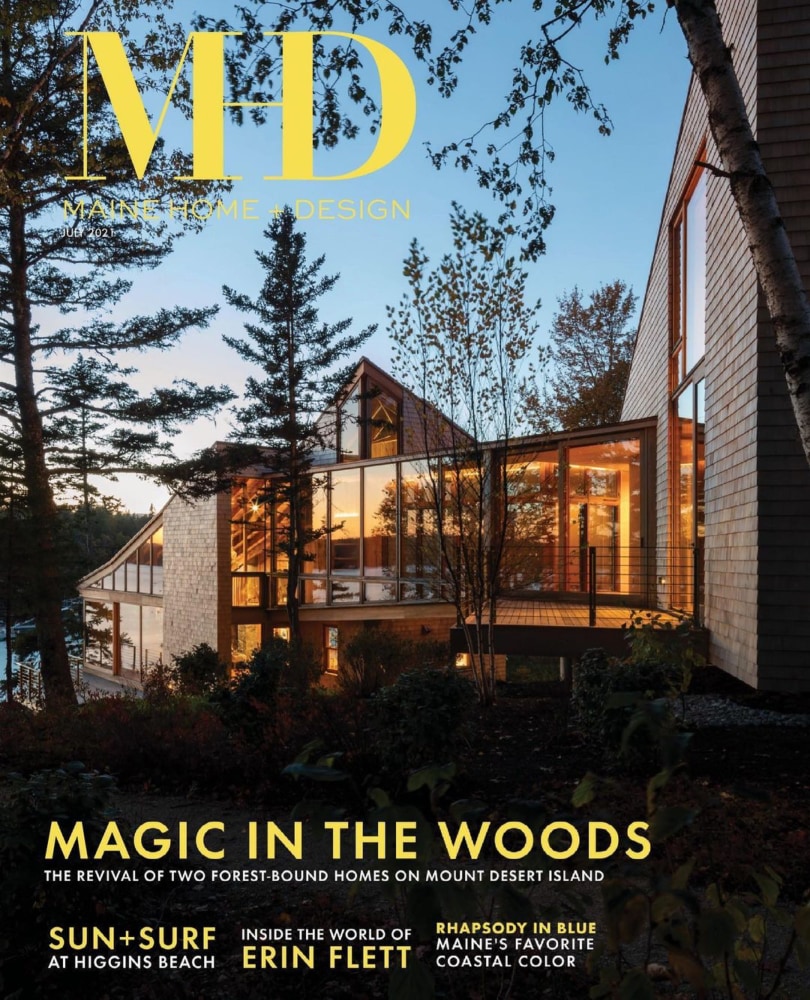

When William (Billy) and Eleanor Lippincott decided to build a summer cottage for their family on Mount Desert Island in the early 1960s, they didn’t want the typical shingle cottage that was so popular at the time. Instead, they turned to Dick Homer, a principal of a Cambridge, Massachusetts–based firm who also had ties to the island. Homer, who earned master’s degrees in engineering and architecture from MIT, worked under the famed architect and Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius, as part of an early iteration of the Architects’ Collaborative, before starting his own firm. The Lippincotts’ home, which was completed in 1965 and was considered radical at the time, consisted of three midcentury modern pavilions—with separate spaces for living, dining, and sleeping, and large expanses of glass—that overlooked the water and was designed to be used only in the summer months.

Fast-forward a little over 50 years to 2017, when a new family purchased the home and hired architect Matthew Baird, the principal of New York–based firm Baird Architects, to restore and modernize it after meeting him through their real estate agent. Baird, who has spent summers on Mount Desert Island for many years (and opened a studio in Northeast Harbor in 2019), was already very familiar with the home and its history, having used it as an inspiration for another home he designed in the area. Baird and the new homeowners quickly realized they shared a similar vision for the home, one that takes its clues from regional culture and that he refers to as “vernacular minimalism.” “They had an interest in simplicity and staying attuned to the initial inspiration of the 1965 house,” he says, “including timeless modernist ideals like extending the spaces of the house into the landscape, while using local materials and reductive design that embraces clean lines.”

The new homeowners wanted to preserve as much of the original home as possible, and they entrusted Baird to work in new elements seamlessly. Baird’s resulting plans called for renovating the main pavilion or “volume,” the building closest to the water, which housed the living and dining areas and kitchen. In addition, they decided to tear down two badly deteriorated upper sleeping pavilions and replace them with one new structure that sits above the main living area and connects with it via an existing glass bridge, which was also rebuilt.

What to save and what to replace were questions that were asked at nearly every step of the project, according to Baird. Ultimately, his approach to preserving the main pavilion was to use the existing interior wooden cladding and to rebuild the exterior portions, including glassing in a porch and adding insulation. “We built a whole new wall structure outside the existing one,” he says. “It’s kind of a new house wrapped around an old house.” He credits Albert Putnam, a local engineer, with reinforcing the original shell to meet current building codes without compromising the structure, which sits on a granite ledge.

In the main pavilion, Baird repositioned the kitchen and living areas to create a large, open-plan space that culminates in a two-story cantilevered corner, with huge, sliding glass panels that open to the water. He also added a Rumford-style fireplace—a tall, shallow structure that efficiently reflects heat—that was constructed using weathered granite salvaged from a nearby quarry. The upstairs portion of the main structure includes a study and powder room, as well as mechanical space and roof access.

The decision to keep the original Douglas fir board-and-batten interior walls and ceilings was an easy one, since they had aged so beautifully, developing what Baird calls “an extraordinary abstract weathering pattern” as a result of moisture seeping in through the old seams and trickling down the wood over the previous half-century. But he replaced the floors and the existing staircase, and he added custom wood-framed Duratherm windows, which expand and contract with the seasons and weather well. A favorite of renowned architect Louis Kahn, the windows are built to withstand challenging climates, such as those in mountain and coastal areas, and require relatively little maintenance.

Baird elected to rebuild the glass bridge that connects the two pavilions and sits above the granite ledge and garden below, installing floor-to-ceiling windows throughout the structure. “I think the windows are stunning,” he says. “They help to create a really compelling space that is dynamic in the house.”

The new pavilion—which replaced the two original “upper” structures, and which houses a new main entrance, mudroom, and laundry room as well as three bedrooms and three bathrooms—features the same Douglas fir walls, ceilings, and floors that were used throughout the lower structure. “In the new volume, all the woodwork was intricately installed by the craftsmen who built the house, Chris Parsons and his crew,” says Baird. “There’s some beautiful work there, all Douglas fir tongue-and-groove, horizontal boards, and the intersections with the windows, the doors, and the corners are quite well resolved.”

In addition to celebrating the original house and maintaining its modernist aesthetic, the homeowners had one other request: they didn’t want air-conditioning. Instead, they preferred to use natural breezes and water temperatures to cool the house. So, in addition to employing passive cooling techniques, such as positioning windows to offer optimal cross-ventilation, Baird installed a whole-house fan in the main pavilion. Last popular in the 1960s and 1970s, whole-house fans draw stale warm air up and force it out through vents at the highest point in the house. This allows cool air to be drawn in at the lowest point of the home, near the water’s edge, creating a draft even when there is no wind, circulating it throughout open areas of the house and, via transoms, over interior doors. Even on the hottest days of summer, explains Baird, the adjacent water rarely rises above 62 degrees, which provides plenty of cooling capacity. Adding a contemporary touch, the architect worked with Altieri Sebor Wieber, a Norwalk, Connecticut–based engineering firm, to design an energy-efficient variable-volume fan that’s powered by a solar array and battery backup system. In fact, thanks to that solar/battery system, the entire house is designed so that it can operate independently of the electrical grid.

Other energy-saving upgrades included installing radiant slab heating throughout the home and the use of warm-dim LED lighting, which dims down to a warmer color temperature, replicating the effect of incandescent bulbs but more efficiently. The sum of these additions means that the home can now be used almost year-round. “The house is wonderfully quiet and secure,” says Baird. “What’s amazing is that it’s so well built that, when the windows are closed and there’s a nor’easter outside, with all this floor-to-ceiling glass you’re really close to the weather—it’s an extraordinary feeling. You’re not watching the weather, it almost feels like you’re in it—but from the warm safety of the living room.”

When it came to the exterior landscape, the homeowners hired Emma Kelly to bring their low-impact, “return to nature” vision to life. Because the site sits within regulatory setbacks that limit the total areas of hardscape or impermeable surfaces that could be added, she and her team had to find creative ways to create paths and entry points, as well as small perches to enjoy the views. “Ultimately, we used the surrounding landscape as a restorative and healing envelope,” she explains, “encouraging a seamless flow of views and experience from inside these incredible glass jewel-box volumes and out into the natural surroundings.”

There wasn’t a need for classic big outdoor gathering spaces, she adds, because the house and its indoor-outdoor rooms really lived an outdoor life already. Instead, she focused on weaving native plants in and around the structures, including native shrubs and sods that will provide “great contrasts of green texture throughout the season.” She also added pops of seasonal color and interest with things like ferns, mosses, huckleberry, blueberries, sumac, and bayberry.

At the waterfront, where the homeowners have direct access for swimming but no dock, Kelly and her team cleared out invasive and non-native plants. They added native sods and shrubs to give the home a “wonderful green frame,” as well as a textured edge for privacy.

For Baird, when all is said and done, one of the best design decisions was creating the open cantilevered corner of glass in the living room. As he explains, when the doors are opened, the living room is essentially outdoors, with 20-foot floor-to-ceiling glass and open air views, right on the water. “Dissolving the perimeter that way, it just makes for such a great contrast between the wild exterior and the refined interior,” he says. Describing the view from the kitchen, looking back through the dining and living rooms, he explains that the enclosure of the house simply falls away. “It feels like you’re on a boat and you can’t see any ground. All you can see is water and sky,” he says. “That’s definitely my favorite part of the house.”

Photography: Elizabeth Felicella